Impact Stories

Protecting Watersheds and Ancestral Domain

Posted on February 6, 2015|

Project Title: Pulangi Watershed Integrated NGO-PO Community-based Resource Management Project (PULWIN-CBRMP)

Year: 1999

Grant Type: Site-focused

Site: Cabanglasan and Malaybalay City, Bukidnon

Proponents: Philippine Eagle Foundation, Inc. (PEFI) and Bukidnon-Higaonon Tribal Association (BUHITA)

|

When the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) came out with its Administrative Order No. 02 in 1992, which provides for the recognition of the indigenous people's rights over their ancestral domain, several indigenous peoples’ communities from various parts of the Philippines submitted petitions for their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim (CADC).

The Upper Pulangi indigenous communities from the Province of Bukidnon were among those who trooped to the DENR Office to submit their claims. There were numerous claims, as they were submitted on a per community and clan basis. Thus, the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Officer (PENRO) of the Province of Bukidnon suggested that the claims be unified to expedite the processing of the ancestral domain claims. This process of unification of claims necessitated the bringing together of the claimants into one single people's organization. Thus, the Bukidnon-Higaonon Tribal Association (BUHITA) was born.

From 1996 to 1999, BUHITA conducted the preparations for the Ancestral Domain Management Plan (ADMP). In 1999, the organization participated in the Pulangi-wide consultation on biodiversity conservation and sustainable development initiated by the Philippine Eagle Foundation, Inc. (PEFI), and the Foundation for the Philippine Environment (FPE).

Preparations for the Community-Based Resource Management (CBRM) Project began in the year 2000. This process eventually gave birth to the PULWIN (Pulangi Watershed Integrated NGO-PO) Project.

The year 2001 saw the commencement of the PULWIN Project's Formation Stage. It moved on to the Strengthening Phase and since 2006, the project has been in transition towards the PO-Managed Phase.

The Project is Significant on Many Counts

The PULWIN Project is a civil society initiative that contributed to the realization of the government's National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP). Formulated in 1995, a few years after the Philippines signed the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the NBSAP set forth the country's strategies and actions for conserving biodiversity emphasizing the community-based management approach. In 2001, the Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priority-setting Program (PBCPP) drew up a list of priority geographical areas for biodiversity conservation, naming two sites covered by the Mt Tago and PULWIN Project.

The Pulangi Watershed is home to endangered species, such as the Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) and a number of endemic and threatened wildlife and plant species like deer, wild pigs, hornbills, tarsiers, owls, freshwater eels, dipterocarps (e.g. apitong, lauan, and almaciga), pitcher plant, ferns, and wild abaca. It is also home to the Higaonons and Bukidnons, indigenous peoples of Mindanao. Upper Pulangi is also a place where some of the remaining forest blocks in Mindanao stand,1 the Mt. Tago Range and Pulangi River.

Both are classified as Extremely High2 critical areas which require immediate conservation plans and actions, including the allocation of high levels of resources and the creation of a favorable policy environment for conservation to prosper. Mt Tago is part of the Central Mindanao biodiversity corridor while Pulangi River is within the Kitanglad-Ligawasan corridor.

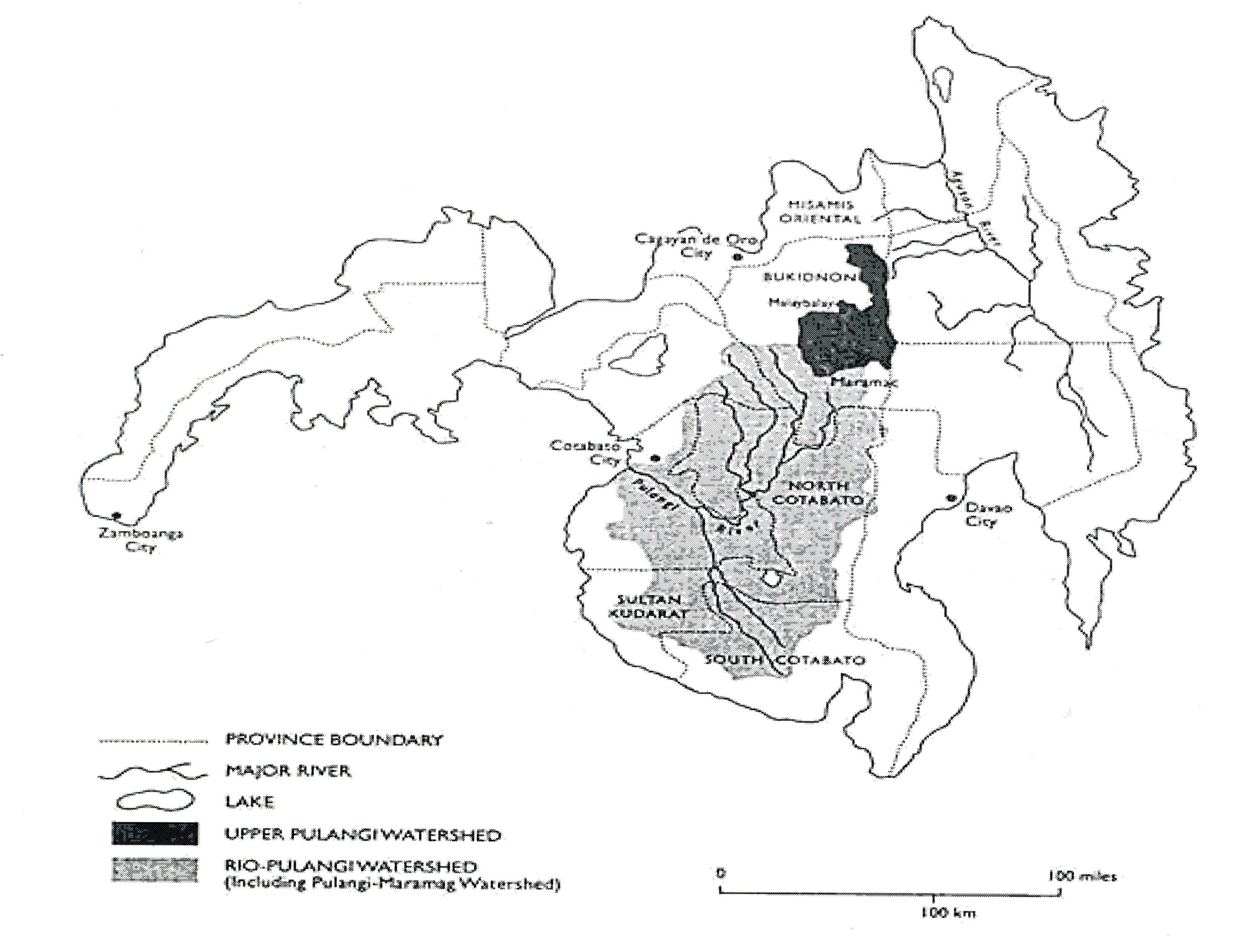

Figure 1.The Upper Pulangi Watershed (Source: http://www.communityforestryinternational.org/publications/research_reports/upland_philippine_communities/index.htm)

The Upper Pulangi watershed [See Figure 1] has been severely degraded. Only the whole eastern and southeastern borders of Bukidnon adjoining Agusan Del Sur and Davao del Norte, which is the focus of the project, remain densely forested. Much of the logged-over secondary forests at lower elevations are progressively denuded as a result of increased clearing for unsustainable cultivation practices and cyclical fires.3

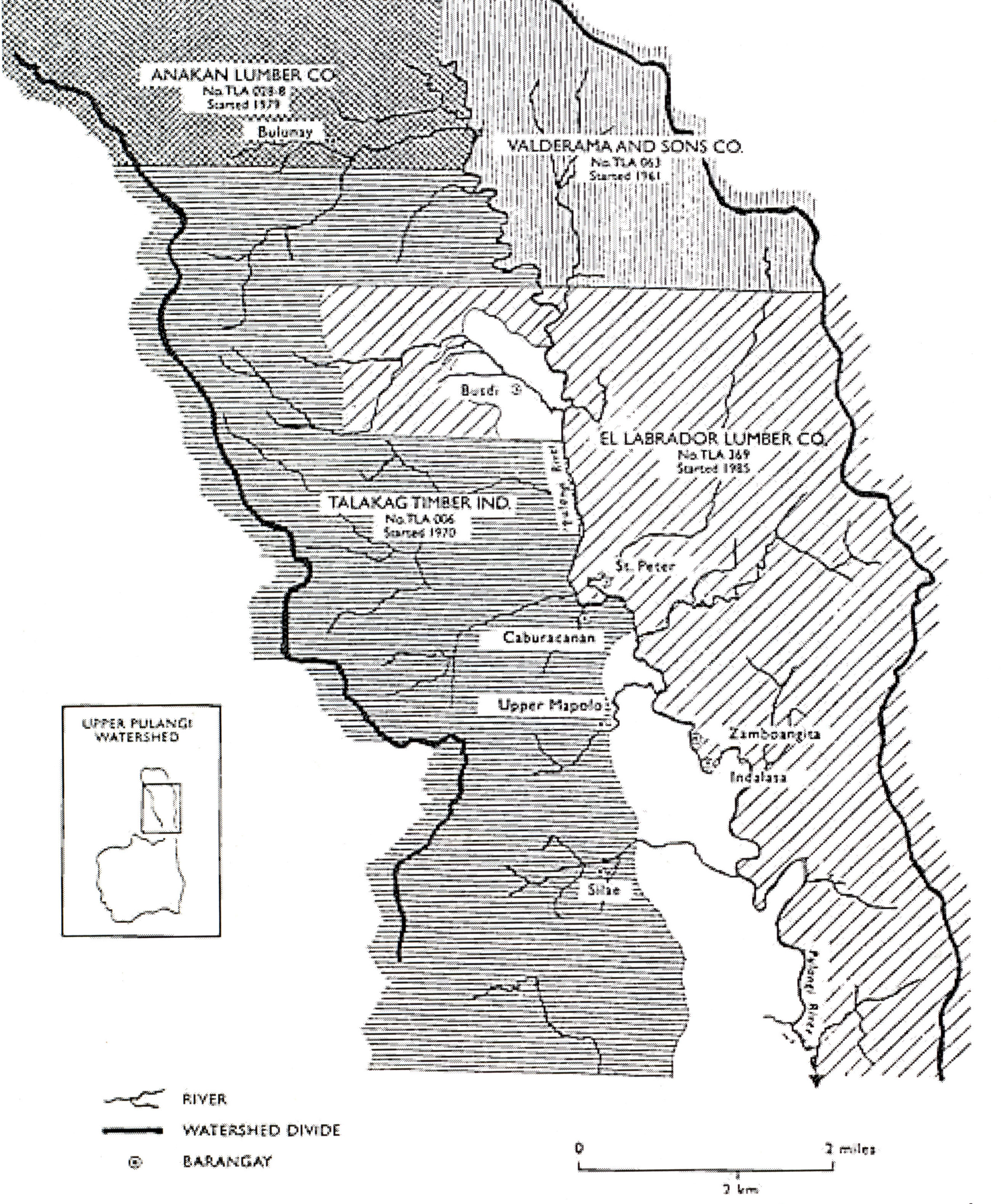

Culprits to this denudation were American timber firms such as Weyerhauser, Georgia-Pacific, Boise Cascade, and Findlay Millar, which cut logs from most of Upper Pulangi's dipterocarp forests in the 1940s and up to the 1950s. From the 1960s onwards, four Filipino logging concessionaires (Valderama and Sons Co, Anakan Lumber Co, Talakag Timber Industries, and El Labrador Lumber Co) armed with timber license agreements came in to finish off what was left [See Figure 2].

Figure 2. Filipino logging concessionaires logging in the Upper Pulangi Watershed in the 1960s onwards. (Source: http://www.communityforestryinternational.org/publications/research_reports/upland_philippine_communities/index.htm)

This 3,100 sq. km. watershed, also called the Upper Pulangi River Basin, which covers seven municipalities and two cities in Bukidnon, bears enormous economic and ecological values. It provides water for agriculture, including agribusiness ventures like the 14,000 hectare Del Monte pineapple plantation and the Bukidnon Sugar Central.4 It likewise supports the Pulangi V Hydro-electric Power Plant in Maramag, Bukidnon which supplies electricity to southern Mindanao.

This portion of the Upper Pulangi, which flows through a narrow valley, is a crucial catchment area for the larger Pulangi Basin5 which covers an area of 1.8 millionhectares.6 Malaybalay, the project host city, plays a strategic role in the protection of the headwaters of the Pulangi and the Tagoloan Rivers because of its location in the upper portion of both watershed areas. The Pulangi River extends through the Cotabato provinces as the Rio Grande de Mindanao and to Cotabato City where it empties into Illana Bay. The Tagoloan River, on the other hand, traverses northwestward towards Tagoloan, Misamis Oriental,where it joins Macajalar Bay. These watershed areas provide potable water, irrigation, hydro-electricpower, and various recreation and tourism activities.

The PULWIN Project, especially with its capacity-building thrust and its forest patrol and reforestation efforts, heeds the call to help avert our country's "biodiversity crisis of unparalleled magnitude."7 Alarm bells had been rung by the government as early as 1987. The Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities (PBCPP) Final Report describes the richness, but also, the dire conditions of Philippine biodiversity, and the urgency of the situation:

“...The country has more than 52,177 described species, of which more than half are found nowhere else in the world... The Philippines is considered one of 17 megadiversity countries, which together contain 70 to 80% of the global diversity... More than 93% of the Philippines' original forest cover has been lost in the last 500 years and 418 threatened species already are listed in the 2000 IUCN (World Center for Conservation) Red List. It is one of the 25 global diversity hotspots... The variety of life found only in the Philippines is threatened with extinction... There is a small window of opportunity in which it is still possible to save this global hotspot from complete devastation and the unique life forms found within from extinction."

How the PULWIN Project Ran

Soon after identifying the Pulangi Watershed as one of its nineteen "priority sites" for biodiversity conservation in 1995, FPE moved swiftly to realize an in situ intervention in the said area. It sponsored major preparatory activities8 from 1996 to identify local partners, do baseline studies, and formulate a conservation strategy for the Pulangi Watershed. BUHITA was chosen as beneficiary-partner organization.

The partner communities live in six barangays9 of Malaybalay City and the municipality of Cabanglasan in the western part of the Pulangi watershed. The barangays are located inside the BUHITA ancestral domain of 29,575.28 hectares located in the northeastern part of Bukidnon. The boundaries of the ancestral domain covered by Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim (CADC) 161 are: Pulangi River in the east; Mt Tago and lmpagsug-ong town in the north; Tagoloan River in the west; and the riceland areas of Malaybalay city in the south. From the six barangays which composed the original area of operation until the strengthening stage of this project, covered barangays have been expanded to 12 barangays to cover 20 gaops (or clans) of BUHITA consisting of three talugans (divisions of cluster of claimants), namely, Upper Pulangi, Lower Tagoloan and Upper Sawaga. This expansion strategically came about in 2006 when the project was on its way to transition – from NGO-managed to PO-managed stage – to consider the development and empowerment of the gaops rather than the intervention to be confined only to BUHITA as an organization.

The population in the project site is slightly over 8,000 persons or 1,600 households.10 They are mostly from the Higaonon tribe. It has been reported that the indigenous peoples who call themselves Higaonon, meaning "mountain dwellers," live in the uplands of northern Mindanao, particularly on the plateaus of Bukidnon,11 on mountain areas of Misamis Oriental and the highland ridges of the Agusan and Lanao provinces. They are one of the least known ethnolinguistic groups in North-Central Mindanao.12 Most are engaged in subsistence agriculture and gathering of forest products. Household income is usually low, ranging from PhP 500 to PhP 4,000 monthly.

BUHITA members cooperate to prepare seedlings for the "rainforestation" project initiated by the PULWIN program to rehabilitate the Upper Pulangi Watershed. (FPE/Aivan Herzano)

The ultimate objective of the PULWIN project was to build self-reliant and self-sustaining communities and to enable them to implement biodiversity conservation projects and to "maintain and enhance the ecological integrity of the Pulangi Watershed."13 Thus, the PULWIN project was born, with PEFI as the project proponent and BUHITA as beneficiary partner-organization. Depletion and degradation were already occurring in the area due to a number of factors.

The following factors were identified by the partner: large-scale and small scale logging; conversion of forest lands into grasslands and cultivation lands; subsistence upland farming that pressed relentlessly into the headwaters of all river catchment; the impact of rapid rainfall runoff and severe soil erosion evident in flash floods, landslides and siltation; worsening rural poverty and economic disenfranchisement among the Higaonons and tenured migrants; landlessness and absence of tenurial security instruments that led to a situation of open access; continued use of unsustainable farming practices among upland farmers; and population pressures due to historically high rate of in-migration.

The main strategy was to employ Community-Based Resource Management (CBRM) by organizing, mobilizing, and strengthening the indigenous peoples in the Upper Pulangi area. Specifically, the project sought to:

- Strengthen the BUHITA in terms of its organizational capability in order to increase its effectiveness in undertaking biodiversity conservation measures;

- Enhance resource management through reforestation and demonstration farming;

- Develop livelihood programs that reduce pressure on critical areas of the watershed; and

- Influence policies by nurturing favorable relations with key stakeholders.

A key element of these strategies was assisting BUHITA in its assertion of its rights over the ancestral domain. With BUHITA having tenurial rights over specific areas in the Upper Pulangi watershed,the communities would be in a better position to push through with environmental rehabilitation and regeneration measures. The project's desired results included the following:

- Strong IP organization (BUHITA) that exercises management and control over their Ancestral Domain, and undertakes measures for biodiversity conservation;

- Sustained biodiversity conservation effort,and rehabilitation of the watershed and enhanced community practices in resource utilization and management;

- Improved living conditions of the communities through increased income generation froma variety of alternative livelihood activities;

- Favorable network of relationships that provide broad supportto the IP's efforts for environmental regeneration and biodiversity conservation; and

- A favorable policy environment at the local level that would open up opportunities for mainstreaming Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Development (BCSD).

Phase I (2001 to 2003)

During Phase One, intensive capacity-building was undertaken covering the following four components: (a) institution building / community organizing; (b) resource management; (c) livelihood development; and (d) advocacy. Monthly classes for the 35-member BUHITA Council of Elders representing 20 clans or gaops were held to enhance the skills of IP community leaders, and members for biodiversity conservation project, managed and engaged in environmental governance. Topics included the following: leadership skills and values, organizational management, the Indigenous People's Rights Act (IPRA), the Local Government Code, forestry laws, para-legal skills, gender sensitivity, sustainable agriculture and agro-forestry (SA-AF), community-based resource management, abaca production and marketing, basic advocacy, project administration and accounting, and the BUHITA Ancestral Domain Plan.

Consultations with village tribal councils were conducted in the six communities. Follow-up meetings were organized to plan CBRM activities. Tribal councils were assisted and closely guided in the implementation of their activities.Working committees were formed and SA-AF demonstration farms and plant nurseries were set up in each of the six communities. Tree planting and abaca farming followed. Forest protection committees were organized and forest patrol gears were purchased. IEC materials on the ancestral domain management plan, on IPRA, and biodiversity conservation were produced and distributed. BUHITA leaders' proactive engagement with local government units gained accreditation and earned seats for the organization in various government structures such as the Provincial Peace and Order Council, Multi-sectoral Forum, Bukidnon Watershed Planning and Development Committee, Technical Working Group of the City Council on the Kibalabag Watershed Project, among others.

The project also allotted time and resources for IP cultural and political strengthening through Cultural Summits. The summits also served as avenues for gathering data needed for CADT application such as population census, genealogy survey, community testimonies, documentation of customary laws and practices.

Phase 2 (2004-2006)14

With a very productive First Phase, the central thrusts under Phase Two or Strengthening Stage focused on organizational strengthening, expanding and sustaining what had been started, diversifying, and preparing to hand over project responsibility from PEFI to BUHITA.

Attention was directed towards regularizing the meetings of the Council of Elders, the Barangay and Sitio Tribal Councils, the working committees, the forest patrols, and the project support staff. This consolidation effort involved the following: a) formation of BUHITA project team, b) installation of the BUHITA financial system, c) review and validation of ancestral domain policies, and organizational systems and procedures (including monitoring and evaluation), d) on-the-job training of the BUHITA project team; and e) development of BUHITA second line leaders. Additional education sessions to address specific needs were also conducted.

Committed leaders and working committees tended well the SA-AF farms, central nurseries, and reforestation sites. Individual families looked after their own backyard nurseries. Reforestation areas were expanded, where it was possible, to compensate for mortalities due to natural causes (drought, soil infertility) and in areas which could not be maintained because of peace and order problems.

By the end of Phase Two, a five-year strategic plan had been formulated by BUHITA and the project had accomplished the following: 38 to 40 hectares of reforested land, three central nurseries producing approximately 11,000 to 14,000 seedlings of assorted species annually, four SA-AF farms planted with seasonal root crops and vegetables, and 2,000 hectares declared by seven gaops as protected forest and 400 hectares as production forest.

The forest patrols or bantay gubat teams in 14 barangays of the ancestral domain were alwayson careful watch for bush fires, poachers and encroachments by outsiders. They also ably assisted in the conduct of perimeter surveys and in setting CADT monuments in their home bases.

In terms of livelihood development, however, aside from taking care of 10 hectares of abaca farms, other income generating ventures were explored. Livestock dispersal hardly took off; only 18 heads of goats and 24 piglets were handed for caretaking in the six communities. Abaca loom weaving and production of abaca crafts did not prosper. Native Higaonon wine production and marketing were wrought with problems like substandard packaging, difficult transportation and low sales.

PEFI and BUHITA's advocacy work soared during this period. The Council of Elders and village tribal councils consciously sought accreditation and representation in local government bodies. PEFI and BUHITA representatives sat in various special local government bodies such as: a) review committee of the Malaybalay City Comprehensive Land Use Plan; b) Bukidnon Watershed Protection and Development Council; c) Technical Advisory Council to finalize the Bukidnon Environmental Code Implementing Rules and Regulations. They also participated in meetings of government and non-government bodies such as the Provincial and City Development Councils, NCIP-Provincial Consultative Body, Local Peace and Order Councils, NGO Sectors' Forum, Regional Forum on Comprehensive Peace, and the Mindanao Peoples' Caucus.

Follow-up work for their CADT application went on high gear. Ancestral Domain Management planning workshops were held in various BUHITA communities. In December 2005, the Regional Ancestral Domain Team of NCIP endorsed the BUHITA application to the NCIP Commission en bane for deliberation. BUHITA territory increased to 36,000 hectares from the original claim of 27,000 hectares.

Information materials on IP rights and biodiversity conservation were produced in various forms: a) four large billboards installed in strategic areas of the ancestral domain; b) one-minute radio spot on the importance of the Pulangi watershed, aired twice daily for two months in a local radio station; c) poster-calendars; and d) organizational manuals distributed in BUHITA areas.

Since the project and BUHITA made their mark in Bukidnon, entities (both government and private) wanting to operate or make use of resources within the ancestral domain now have to pass through BUHITA scrutiny. With the respect they have gained BUHITA has triumphantly asserted its right to render free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) over proposed undertakings in their ancestral territory. The recognition bestowed on BUHITA even translates into financial gain for the IP communities through a share they get from the proceeds of the said economic and service projects.

All these are covered by a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between BUHITA, the city government and the City Water District regarding the allocation of proceeds from the sale of water to the municipality. The MOA provides for a payment to BUHITA and Barangay Kibalabag the amount of six centavos per cubic meter of water consumed. This arrangement is in recognition of the municipality's obligation to compensate them for the development of the area for the water system project. Amount received range from PhP 18,000 to PhP 65,000 during the period. This is aside from the free water services for selected tribal communities in the BUHITA ancestral domain.

Crises and Responses

In the early years of BUHITA until around 2004, there were protests against its ancestral domain claim. These protests were mounted by tribal people, who were indifferent to the leadership of BUHITA, and politicians who were threatened by BUHITA's aggressiveness.

BUHITA responded by launching information campaigns about the claims and engaging in dialogues and negotiations. This process somehow helped diffused the protest. But the biggest blow against those who stood in the way of BUHITA was the NCIP's announcement that BUHITA's CADT application is the commission's top priority. Today community members and politicians have expressed support for BUHITA's CADT claim.

A Sense of Being Able to Effect Change

Technically, BUHITA may appear like a typical people's organization. BUHITA is able to mobilize people in the community to address issues affecting the ancestral domain and the environment. This is so because BUHITA is not a simple PO; it also represents aspects of the traditional tribal structure where tribal elders provide leadership over the whole community.

The mobilization of the community through the project, and under the banner of BUHITA, has nurtured a sense of being able to effect change – a sense of being able to do something. An instance is when the seven gaops in Can-ayan who declared 2,000 hectares of forest as protected forest. Another case is when the organization asserted their rights over their ancestral domain by requiring the City Government to conduct consultations in the communities regarding the water project in Kibalabag. This process eventually led to the forging of a MOA between BUHITA, the city government and the City Water District that essentially provides payment for environmental services (PES) to BUHITA.

With BUHITA's consistent assertion of the rights of the indigenous people, it has transformed itself into a distinct platform around which the Bukidnon-Higaonon can rally behind and make themselves heard. From all indications, this, by far, is the greatest achievement of the project. By strengthening BUHITA and enabling it to articulate the aspirations and agenda of the indigenous people, the project has established and mobilized a potent vehicle for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

However, as regards the role of communities in environmental governance, the project's limitations and shortfalls can be discerned. While lobbying and advocacy at the city and provincial levels are commendable, the project has been unable to effect major changes at the level of barangay governments.The gaops are pursuing environmental protection and undertaking forest guarding. Indeed, the project seems to have minimal impact on production systems, except perhaps, for the reduction in slash-and-burn agriculture.

Challenges

The Association of Upper Pulangi Barangays does not appear to have taken as an urgent agenda the rehabilitation and protection of the Upper Pulangi area. It is apparent that cultivation of hilly and steep areas continues to be a practice.

Agricultural production in these communities continues to pose serious threats to the whole ecosystem. Had the barangay governments been mobilized for BCSD, perhaps an Upper Pulangi-wide ordinance on agricultural production could have been formulated and enforced. The enforcement of such ordinance would have helped prevent further massive erosion, landslides, and siltation of the Pulangi River.

Indeed, a major technique employed by the project to promote BCSD among farmers is demonstration farming. There are four demonstration farms for sustainable agriculture – agro-forestry. The main characteristic of these demo farms is that these are diversified and integrated farms. Yet, in the communities, mono-cropping has remained the dominant production system. The demo farms seem to have little impact. Or they have failed to capture the interest of the farmers. While the project has gradually made a dent in terms of raising environmental awareness, such awareness has to be translated into guarding their domain against the exploitation of outsiders in the guise of development.

Conclusion

On the whole, the assessment of the project's significance has to be viewed through the lens of CBRM as a framework and strategy, as well as, through the lens of IP governance and development principles. During the last seven years (2000 to 2007) the focus of the project has been on strengthening and capacitating BUHITA as a people's organization, and enabling it to realize its quest for a certificate of ancestral domain title (CADT). In short, the bias of the intervention has been on organizational development and strengthening and enhancing the tenurial security of the IPs in the Upper Pulangi and Upper Tagoloan watersheds. A major chunk of advocacy efforts was also directed towards hastening the process of recognition of ancestral domain rights. This could, perhaps, explain why results in the resource management and livelihood development components are still limited.

The bias towards CADT and PO-building is premised on the view that CBRM cannot succeed unless tenurial instruments are obtained and people are secure in the land. Furthermore, this can only beachieved if the organization of the IPs is strong enough to withstand all the pressures and overcome the challenges and capable enough to comply with all the requirement of CADT application and processing.

In terms of PO building, the project has been successful. However, there is a need to carefully evaluate the readiness of BUHITA to undertake bigger responsibilities.

While BUHITA may have already acquired relevant knowledge and skills in PO and project management, its capacity to govern and manage a vast territory such as the 36,000-hectare CADT area is still a major question that needs to be explored. This becomes even more critical considering that existing within the territory are institutions and government units whose constituencies, priorities and agenda may differ from that of BUHITA.

The remaining challenge is the question regarding the appropriateness of the people's organization as the manager of the ancestral domain. Given that BUHITA is a membership-based organization (PO); would it not be appropriate that a confederation of tribal councils or a confederation of gaops be organized to serve as the overall governing body of the domain? And what might be the role of other rural institutions like the barangay government units and other residents in the watershed who do not belong to the Bukidnon-Higaonon tribe? These and other issues need to be explored towards truly preparing the communities in the management of the domain.

What the project could truly be proud of is the fact that it has restored within and among the Bukidnon-Higaonon people in the project site a sense of dignity and cohesiveness, two important values that could be translated into one term: empowerment. Another important feature of the project is that it has introduced biodiversity conservation and environmental protection as a major development agenda in the project site. As one leader pointed out, care for the environment is a value that has been nurtured and popularized by the project so that ordinary people in the communities have recognized the need to address the environmental problems they are facing.

Pantaron Range, viewed from Malaybalay and San Fernando, Bukidnon. (Juland Suazo)

The intervention in Pulangi is extremely important because it is being undertaken at a time when pressures on the natural environment have intensified owing to the highly extractive production systems on the one hand, and the pressures of poverty and economic disenfranchisement, on the other.

The two-fold focus of the project, that is, biodiversity conservation and IP rights over ancestral domain and biodiversity conservation, is a major theme that is relevant not only to Mindanao but to other parts of the world where indigenous peoples are also struggling for greater recognition, and whose relationship with the natural environment had been undermined by the onslaught of industrial development and modernization. The lessons that could be generated from this project could be used to sharpen the discourse on IP rights, environmental governance, and biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

The project, despite modest resources relative to the size of the area, created an enduring impact on the Higaonons and Bukidnons themselves. It has already laid the foundations for institutionalizing measures for biodiversity conservation.

Biodiversity conservation and sustainable development is a multi-stakeholder concern that involves a complex web of factors and variables ranging from policy issues, political relations and dynamics, cultural and sociological factors, the logic and organization, the objectives of economic production and the way production is organized, including the technology employed in the production of goods and commodities. Indeed, BCSD is a complex challenge that can only be addressed through a comprehensive approach where key stakeholders are mobilized.

In the case of the PULWIN Project, emphasis was on the organization of the indigenous people and on the IPs' quest for control over their ancestral domains. The project is premised on the assertion that the IPs' enhanced tenurial rights will lead to a favorable condition for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. While such assertion may have a basis there have been instances ancestral domains have been offered by IP leaders to mining companies, mono-crop growers, and other commercial operations that may be detrimental to the environment, and therefore unsustainable. This only shows that tenurial security, such as the certificate of ancestral domain title and the biodiversity conservation and sustainable development, one does not automatically lead to the other.

For as long as the logic of economic production is dominated by the satisfaction of the market and where sustainability is measured in terms of competitiveness in the open liberalized market, the threat to the natural environment will always be there.

- National Statistics Office. 2002.

- Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities. 2002.

- "Project Status Report for the period April 01-June 30, 2000," report submitted by the Philippine Eagle Foundation to the Foundation for the Philippine Environment, 2.

- "PULWIN-CRMP Phase 2, Year 1 Terminal Report (August 2004 -August 2005)," report submitted to theFoundation tor the Philippine Environment.

- "PULWIN-CRMP Phase 2, Year 2 Terminal Report (September 2005-September 2006)," report submitted to theFoundation for the Philippine Environment.

- http://www.community forestryinternational.org/publications/research_reports/upland_Philippine_communities_index.htm

- http://www.pcarrd.dost.gov.ph/cin/watershed/r&d.htm

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malaybalay_City

- http://www.adb/org/Documents/Reports/lndigenous_peoples/PHI/indigenous_phi.pdf

- http://www.ncca.gov.ph/ORGANIZATION/SCCTA/SOUTHERN/southern_higaonon.htm

DISPLAY CALENDAR

DISPLAY CALENDAR

Read Policy Briefs

Read Policy Briefs

View Our Partners

View Our Partners

Access Grants MIS

Access Grants MIS

Login to Webmail

Login to Webmail